Growing up with OCD teaches a person to anticipate problems, which teaches them to problem solve at an early age. When most people hear the acronym OCD, they assume it is all about repetition – counting, organizing, and cleaning most famously. In actuality, that is just the typical manifestation of the the actual symptoms of OCD, the “compulsive” part of OCD. These are simply the form of rituals the person dealing with OCD is using to self-soothe their need to anticipate problems. Rituals all come down to the need to control one’s environment. The “obsessive” part of obsessive compulsive disorder is from the cycle of worry that stems from a fear of not being able to anticipate a problem.

A person with OCD may have a fear about their alarm clock not going off and being late for work. But, making sure that the alarm is set properly before they go to bed simply isn’t enough to quell that fear. What if they weren’t paying attention and accidentally set the alarm for PM instead of AM? What if they didn’t really flick the switch over all the way, and it doesn’t go off, or is set to radio, which is too quiet to wake them up? Of course, there is also the completely unavoidable problem of the power going out, which can only be solved with a backup system of generators… but even I’m not that paranoid. So, to anticipate these problems, they may check the alarm again, and again… and again and again and again, at least until they have soothed that worry enough to go to sleep.

The irony of being a writer with OCD is that even though I live my life trying anticipate problems that will trigger my anxiety, which leads to countless ways of trying to foresee how a situation with turn out, I am a particularly rigid and linear writer when plotting scenes.

“Then, I discovered the key to solving this problem simply by doing a quintessential nerd thing – playing DnD.”

When plotting out my seven major points in a story, I have no problem deciding exactly how and where I will introduce conflict and steadily working towards the resolution. The issue comes when I need to work on a smaller scale, linking the individual seven points together, or even smaller, from the beginning of a conflict within a scene to the scene’s resolution. The in-between parts are looser, more flexible, and need to contain more focus on the characters emotions. Plot occurs between the seven major points in the main story arc, but character development, which is the steering wheel for plot, meaning this is how story moves forward.

Keeping readers on their toes is incredibly important. If the story becomes predictable then readers lose interest. If they can predict what the characters are going to do, they get bored because they have already read this story. But, creating seemingly random variations in the outcome of a situation always felt like a dead end. If I knew what needed to happen at the end of a scene it felt impossible to not work towards it, even if I wasn’t convinced it was the best way to move the story forward, but was the only idea I could generate to finish the scene. And, if this was the only idea I could come up with, I found it even harder to work through the actual scene itself. I knew how a scene would start, and I had decided how I thought it needed to end, but how do I get from point A to point B in this scene without writing directly to resolve the scene. How can I work in the all important character development layers in the scene needed to feel like the plot is moving forward, even if we are just reading the internal monologue of a character dealing with the aftermath of an important plot point.

“You want to explore as many options as possible, even ones that may seem counter to your objective, because you never know the connections that will form between the ideas once your imagination takes hold.”

Then, I discovered the key to solving this problem simply by doing a quintessential nerd thing – playing DnD. Recently, I started playing Dungeons and Dragons again after a very long hiatus, creating a new group from my work friends. One of my best friends and fellow teacher, Dylan Power, joined the party as a player, but usually DMs (Dungeon Masters – the equivalent of Game Master for other tabletop RPGs). Recently, we started writing together in order to bounce ideas off each other – he plotting his campaigns while I work on my fiction, and I have discovered that he is an incredible DnD storyline writer. The reason he is a fantastic story line writer is because he has the ability to generate various outcomes of any situation he puts his player in during game play.

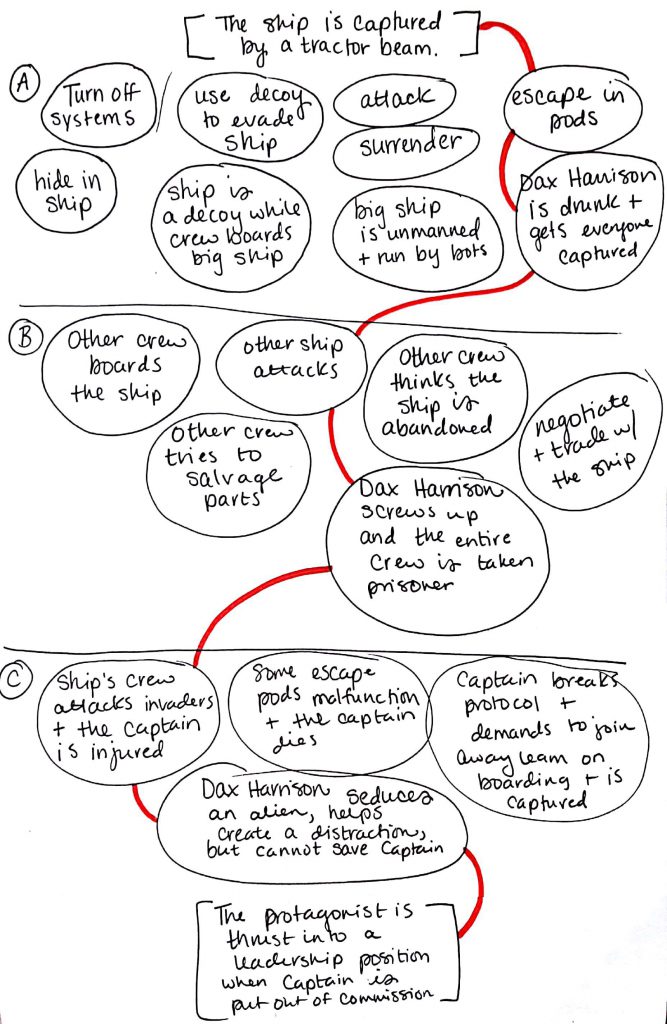

During one of our writing sessions, I watched him plot out his story map for the first leg of the campaign, and was stricken with envy. Much like I would have done when plotting a scene, he determined a starting point and an endpoint (conflict and resolution), but what he did in between was completely different than to my normal writing process. From the start point, he would write out a chain of events stemming from not one, but up to four ideas.

“Plot occurs between the seven major points in the main story arc, but character development, which is the steering wheel for plot, is how story moves forward.”

Begging him to teach me his dark form of idea generating magic, lamenting my situation concerning my inherent need to problem solve and plan for all contingencies, I stated how frustrating it was that I couldn’t easily do this same thing when writing scenes. And his response was so stupidly simple, I actually felt like an idiot when he pointed it out:

“Well, I have to account for people. You’re trying to account for things.”

Brick wall, meet face. It was so obvious. I was doing everything wrong… even though, he wasn’t entirely correct. Plot is driven by the actions made by characters who are constantly developing, changing, and evolving. This means that whether I am trying to plot a scene, a story arc, or the arc of a trilogy, none of this can be done without accounting for variables created by character decision making.

Using Role Playing Story Mechanics to Plot:

Try to pick a scene that you have not plotted yet. The less you have plotted the better – it prevents you from thinking too narrowly or linearly. You want to explore as many options as possible, even ones that may seem counter to your objective, because you never know the connections that will form between the ideas once your imagination takes hold. Give yourself permission to jump around and be spontaneous. Right down every possible scenario, even the ones that don’t make sense.

Steps:

- Choose inciting incident and a conflict to be resolved by the end of the scene

- Brainstorm as many possible causes and effects from the inciting incident, as well as obstacles created. Think specifically about the characters involved, and how they will react in the situation presented.

- Continue to connect the cause and effects of the different levels of the unfolding conflict, finding ways to solve obstacles or to connect to the resolution of the conflict. (Unresolved obstacles can be used as foreshadowing or lead to other scenes.)

- Once finished, pick a path from beginning to end. Once chosen, write out the sequence of events you chose in order from beginning to end.

- Huzzah! Now do it again with another scene!

Note: Keep in mind that using this process might through your scene completely out of order. If this happens, it is probably for good reason. This process tends to reveal plot holes and weak spots in plotting. Don’t be afraid to add more to the beginning, the end, or even through out the middle. Also, do not be afraid to cut material out that doesn’t fit with the new idea. Hold on it for later, or write an alternative scene and see which fits better in the long run for the scene or the story arc.

Write on young savior,

No Comments